Hello for the last time,

Today I’m sharing a view on how a Labour Government can reshape Westminster and Whitehall’s China capabilities and approach. I have tried to make it as granular as possible, avoiding cliched sweeping statements - (we’re in a new age of insecurity, globalisation is dead!) - and instead set out potential actions. It is a culmination of nearly four years working in this space.

Many of you reading will have much deeper knowledge and insights into the system I’m writing about. In this case, I gently ask that you view the recommendations in the spirit of what they are meant to be: warm efforts to encourage new ideas and ambition, rather than criticisms of units, teams or ideas I can’t see.

As with all my work, it was not paid for or sponsored by any corporation, foundation or government department, and it was not asked for nor endorsed by Labour. It is a cathartic ending for me, and hopefully an exciting beginning for a handful of fundamental conversations about what needs to change.

I plan on keeping you in the loop with whatever comes next: a new idea or project perhaps. Our podcasts and event schedule will also continue. If you work in Government or politics and want to discuss any of the following points, get in touch. But until then, a final thank you and goodbye.

Foreword

The United Kingdom will have a General Election on July 4th 2024. Current polling suggests the Labour Party will win, likely with a significant majority.

This will give the party a chance to push through legislation it deems a priority, much of which will likely have a domestic focus, reflecting leader Keir Starmer’s six pledges. But the world does not stop at the North Sea, the English Channel or the Atlantic Ocean. And the world is, in many ways, entirely different from some of the dominant narratives in Westminster.

The illegal Russian invasion of Ukraine and the COVID-19 pandemic have proven that events that take place far beyond our borders can impact the lives of millions of people at home in the UK. The domestic response to the Israel-Gaza conflict shows a general public alert to foreign affairs, and Labour appears open to increasing defence spending partly out of recognition of these shifting tectonic plates.

In a highly globalised world, the events of the last five years have cast a harsh light on the UK’s dependencies and supply chain vulnerabilities, from energy, to defence equipment, to medical supplies. In the words of Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves, “we are now living through … an age of insecurity”, in a world in which domestic policy is ever more tightly intertwined with foreign policy in a way that it has not been for decades.

In my view, the UK’s relationship with the People's Republic of China (PRC) is, by some distance, the most complex bilateral the UK Government will have to wrestle with over the next decade. Our relationship with the PRC cuts across every element of society, business and the economy, and - along with the US - the PRC’s actions determine the weather of global geopolitics more broadly.

The PRC is the world’s second-largest economy, as well as one of the UK’s largest trading partners. For much of the last century, the UK’s largest trading partners have historically been like-minded, geographically close, liberal democratic market economies. The PRC is none of these.

This creates an inherent tension between economic realities and moral imperatives for the UK. We must pursue beneficial trade relations with China – for economic growth, job creation, and global stability – while simultaneously upholding democratic values, human rights, and safeguarding our national security and industry. Strength in our convictions, choices and democracy must underpin any engagement or choices we make regarding China. The tension manifests itself in difficult trade-offs - and there will need to be trade-offs.

Clearly, there is an awareness in Labour about the numerous challenges the Chinese Communist Party presents to the United Kingdom’s industrial and international interests. Keir Starmer believes China “shows disdain for democratic values and human rights, and it is seeking to exploit economic leverage”. Shadow Foreign Secretary David Lammy observed earlier this year, “China’s rise … has been matched by greater repression at home and more assertive behaviour abroad and undermined the economic level playing field”. Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves believes the PRC has “undercut and ignored the international trading rules, and made it impossible for our own companies to compete”.

Despite this, the party has been clear that “it is in our national interest to engage with China” – on trade, climate change and global health, among other areas. The current government’s approach has been, at best, inconsistent – from the ‘Golden Era’, and the UK as China’s “best partner in the West”, under David (now Lord) Cameron, to the PRC being deemed “the world’s biggest threat” during the short-lived premiership of Liz Truss. Even the current Prime Minister, Rishi Sunak, has veered from declaring “China and the Chinese Communist Party…the largest threat to Britain and the world’s security and prosperity this century”, to more muted talk of China being an “epoch-defining challenge” within the space of twelve months. As Lammy has observed, “The government is divided and inconsistent on China, flip-flopping between tough talk and muddled actions”.

Whatever approach a Labour government chooses to take with China, part of it must be predicated on (re-)normalising regular Ministerial engagement and frequent bilateral visits. The lack of bilateral visits represents a fundamental failure of UK foreign policy, irrespective of one’s views on China. It puts us at odds with many of our closest partners – in the EU, US, and the Indo-Pacific – who have all had numerous senior-level visits, in both directions, in the intervening period. It leaves the UK open to accusations of just watching from the sidelines. This needs to change.

To achieve this, Beijing To Britain believes we need to put China expertise at the heart of our approach – through meaningful investment, increased ambition and transparency, and much-needed reform of the existing systems and structures – enabling the UK to meet these challenges head-on. Get this right, and the United Kingdom can replicate key elements of this approach with other critical bilateral relationships, such as India, Indonesia, Nigeria, or Brazil. We can rebuild confidence in our ability to understand and influence the world post-Brexit, creating a toolkit that enables politicians to get up-to-date information, and create a Whitehall geared towards hiring, nurturing, rewarding and retaining talent.

The question is ‘how’?

Beijing to Britain has had a ring-side view of UK-China relationship in Parliament for the past three years – our analysis has been cited by numerous media outlets including The Financial Times, Bloomberg, The Guardian and The Economist, and informed three Parliamentary Committee inquiries. Reflecting on numerous conversations throughout Whitehall and Westminster, outside analysts, and those with extensive China experience, this paper puts forward a constructive and provocative vision of how we can – and must - improve our collective approach to the PRC.

It requires a restructuring of how Whitehall and Parliament operate, which can only be pushed through by a Government with the necessary level of ambition and vision, if we are to turn the Shadow Foreign Secretary’s “Progressive Realism” into something that is more than a soundbite.

This paper builds on Labour’s ‘three Cs’ approach:

Challenge

Compete

Cooperate

And adds a further two, which I believe are necessary to enable more effective delivery of any future China strategy:

Create

Communicate

Together, I believe these recommendations can begin to rectify existing issues in our system, establish solid foundations for engagement with China today, and ensure the UK is better equipped to face the challenges of tomorrow in this critical bilateral. Some of the proposals set out in this paper are clearly imperfect – however, they are indicative of the level of ambition needed to drive meaningful change in systems and structures that are institutionally resistant to it. If nothing else, I hope that these proposals will prompt discussions and thoughts on how we can collectively do better – a call to action, rather than a return to the status quo. The United Kingdom can do it.

- Sam Hogg, Founder and Editor of Beijing to Britain

Executive Summary of Key Actions

Create

A new Securonomics Unit to advise the government on an evidence-based, coherent and consistent approach to China as part of its wider remit

Index of Independent China Experts who can be called upon to brief MPs and the press on specific technical aspects of the relationship, or ‘China+’ relationships

Chinese Language and Culture Taskforce to improve UK’s China capabilities and build a pipeline of future leaders in this space

Enhanced cybersecurity measures, implementing advanced cybersecurity protocols and training for all government departments to safeguard sensitive information, aligning with recommendations from GCHQ

Communicate

Create a professional and comprehensive communications function – UK China Communications Centre – which will ensure the UK’s approach to China is communicated to the public, Parliamentarians, media, businesses and academia by subject-matter experts

Publish an unclassified version of Labour’s China strategy

Ensure Ministers in foreign or defence policy remain in their posts for a minimum of two years

Challenge

Conduct a UK-China Audit to identify areas of dependence on China in critical sectors, as well as mitigation strategies

Showcase the impact of sanctions by creating and updating a public Government sanctions dashboard with high-quality data

Evidence the pushback against nefarious CCP activity by publishing an annual update on how many interventions and actions have been made under the National Security Act, and similar mechanisms

Compete

Strengthen the UK’s economic toolkit to respond to acts of economic coercion

Create new engines of economic growth via ‘clustering’ agreements between universities and local businesses all over the country, supported by the UK's new National Wealth Fund

Reform the WTO and enhance standards in trade agreements

Rebuild UK leadership in key multilateral and transnational bodies

Continue to state that China’s entrance to the CPTPP must be conditional on the Auckland Principles being met

Cooperate

Deepen cooperation on climate change and green transition with ‘testbed’ joint projects in third party countries

Establish new bilateral Ministerial-level dialogue on AI and Emerging Technology with particular focus on safety and standards-setting

Launch a consultation with British business on potential future trading relationship with China, but rule out a Free Trade Agreement with the PRC for the foreseeable future

Create

In Beijing to Britain’s view, many of the problems with the UK’s current approach to China are deeply-rooted structural issues. China is a unique, complex and multifaceted challenge that the existing Westminster and Whitehall structures are not addressing effectively, thanks in part to silos. Adding to this complexity is that China changes at a rapid rate - the China of today will not be the same as the one in six months. It will also continue to present opportunities and challenges for decades to come.

Nimble new structures and approaches could be created, as well as significant investment in building China capabilities - from the grassroots up - creating opportunity across the country in the process. What follows is a suggestion for setting up a unit which would cut through the usual bureaucracy and move with speed and expertise: it contains pros and cons.

We suggest:

Create a new Securonomics Unit - potentially as an Executive or Advisory Non-Departmental Public Body, so as to provide a degree of independence, as well as greater flexibility on governance structures and recruitment processes - reporting directly to the Prime Minister’s Office/Cabinet Office, with a significant part of its remit covering China. The Securonomics Unit will:

Have an independent expert Advisory Board, tasked with developing and advising the government on an evidence-based coherent/consistent approach to China.

Take on the current functions of the FCDO China team and Cabinet Office National Security Secretariat China team – seconding in staff from both of those organisations, as well as other government departments across Whitehall.

Be called upon to brief the National Security Council (and its sub-committee on Economic Security) when required.

A priority action of the Securonomics Unit will be a root-and-branch review of existing Civil Service structures/functions/restrictions, with a view to rapidly improve China capability – including the need to:

Review and adjust the secrecy levels of information pertaining to China.

Identify and reduce role duplication in Whitehall.

Incentivise China specialists to remain in or move between China-related departments and roles - whilst also reinstating pay progression within roles, and introducing minimum terms in critical roles to reduce churn.

Incentivise those who speak Mandarin or Cantonese to use their skills within the civil service through innovative ideas such as helping pay off their student loan for each year they utilise their languages or replicating the FCDO’s ‘language supplement’ allowance across all departments for speakers of those languages.

Create meaningful ‘career pathways’ for China specialists, enabling progression and incentives for continuous professional development, in a similar manner to existing ‘professions’ within the Civil Service. Implement the recommendation from the Black, Connolly, Adjerid and Kelsey report - ‘The Crossroads Of Geopolitics: The Intersection Of Security And Economic Interests, Policymaking In A More Complex And Uncertain World’ - to create an economic security cadre within Whitehall.

Give Civil Servants the opportunity to be publicly recognised for their experience and insights, by allowing senior officials to speak more publicly about their remits and roles – providing media training more widely, where necessary.

Implement recommendations set out in think tank Reform’s ‘Making the grade: Prioritising performance in Whitehall’ report, specifically recommendation four: “'Behaviours’ within the Success Profiles should be scrapped in recruitment of external talent. Assessment of candidates should prioritise skills-based tests and actual experience.” The dominance of ‘Behaviours’ over relevant experience and genuine expertise in Civil Service recruitment critically undermines departments’ ability to get the right people in the right roles, especially with respect to China.

The Securonomics Unit would also:

Ensure the UK is better able to respond to acts of economic coercion – either to itself or to allies – by strengthening the UK’s unilateral economic toolkit, developing new tools where appropriate (e.g. EU’s new anti-coercion tool) and establishing formal coordination mechanisms with key allies to better respond to threats, as well as defend UK industry. This would also include a review of the UK’s current tariff and anti-dumping measures. It could source insights from the United States State Department team working on this issue, among others, and should align in many areas with the European Union’s own anti-coercion tool.

On a granular level, a Government landing page could be created aggregating the UK’s current work on countering economic coercion, noting the existence of the National Security Council (Economic Security) sub-committee and outlining the UK’s work within the G7 on this subject. For instance, there is no reason why the evidence submitted by the Cabinet Office discussing the UK’s actions on this issue to date should not be sitting on a Government web page.

It could include one point of contact for external entities to contact the government on this issue.

In addition to the Securonomics Unit, create a new Index of Independent China Experts (IICE) (similar to Independent SAGE) who can be called upon to brief Government Ministers, MPs and the press on specific technical aspects of the relationship, or China’s relationship with other countries (for example - Russia - as called for by the Lords International Relations and Defence Committee).

Some of the Experts should correlate to the areas of concern identified in the UK-China Audit. Others should be closely monitoring China+1 relationships (for example, Sino-Russian relations, Sino-DPRK relations, Sino-United Nations, and Sino-Indian relations.)

The Independent Experts must be diverse, with multiple experts for each identified area. Whilst think tanks and academia can contribute expertise and should be represented, law firms and private sector multinationals contain significant depths of expertise and should be approached.

Should IICE prove effective, the Securonomics Unit could consider utilising them within Five Eyes, and potentially commercialising their expertise.

Create Government-funded scholarship positions to address expertise gaps identified by the UK-China Audit (see below), and second-in talent from the private sector and academia.

Scholarships should be offered on a two-year rolling basis, and potentially funded by the profits made from the Home Office selling passports, which could provide a stable source of income for the programme, for example.

These scholarships could include the seconding-in of staff from appropriately vetted private sector companies on a one- to two-year basis that operate in the sectors identified in the UK-China audit as being areas of focus. Likewise, Civil Service staff identified by the Securonomics Unit should be seconded into the above-cleared list of companies.

Create an annual two-day conference on China bringing together Whitehall, Parliament, media, and business to identify solutions to critical issues in the bilateral, as part of a whole-of-society effort.

Should this be successfully launched, the British Government should use its influence as a convening and acting authority to assemble more frequent Commonwealth meetings, with seats offered on a temporary basis to countries that sit outside the bloc but share common issues.

Teams from across Whitehall, including the Research and Collaboration Advice Team (RCAT) and the Investment Security Unit (ISU) should be given a platform to share their expertise and insights.

While restructuring of Whitehall will be essential, a focus on reforming parts of the Parliamentary system is necessary too.

Parliamentarians - and their staff - have been on the receiving end of numerous Chinese state-linked cyber-attacks and are expected to debate and vote on a wide number of China-related issues. To this end, the Securonomics Unit should work closely with the Parliamentary security teams and Parliamentarians to:

Establish best practices on cyber security: give politicians and staff work devices such as laptops and phones, and provide them with regularly updated virus scanning software. Make this a default, removing this from having to be a politician or researcher applying to IPSA for the phone or laptop, which could end up receiving negative and unfair media coverage.

Create monthly optional briefings from IICE on themed sessions, run alongside the Parliamentary Committee’s International Affairs Unit.

Share best practices and updates with Parliamentarians from other democracies.

Create a system where politicians’ researchers can spend time working at vetted private sector companies or think tanks to learn skills and insights related to this space.

Test MPs, Peers, and their staff on cyber hygiene, with GCHQ and Parliament’s cyber team regularly utilising fake emails or messages to stress-test Parliamentarians given the face of growing risks of cyber-attacks from China.

The arrival of a new Government should mark the start of a period of stability for departments, which will hopefully have a second derivative impact on morale. To this end, it should be a priority to ensure Ministers in foreign or defence policy remain in their posts for a minimum of three years to enable meaningful personal relationships to be built between the UK and China, at the most senior levels, and consistent open lines of communication.

Similarly, the precedent should be set for a Prime Minister to spend half a day every fortnight meeting with Ambassadors stationed in London from around the world, particularly from nations outside the European Union and the G7. Many Indo-Pacific, African and South American countries send their top officials to be Ambassadors to the United Kingdom, and they should be met and appreciated as such.

The UK’s lack of China expertise and capacity is an issue the current Government is aware of, and funding has doubled. But it should be restructured from the bottom up - our current lack of expertise represents a fundamental national security risk.

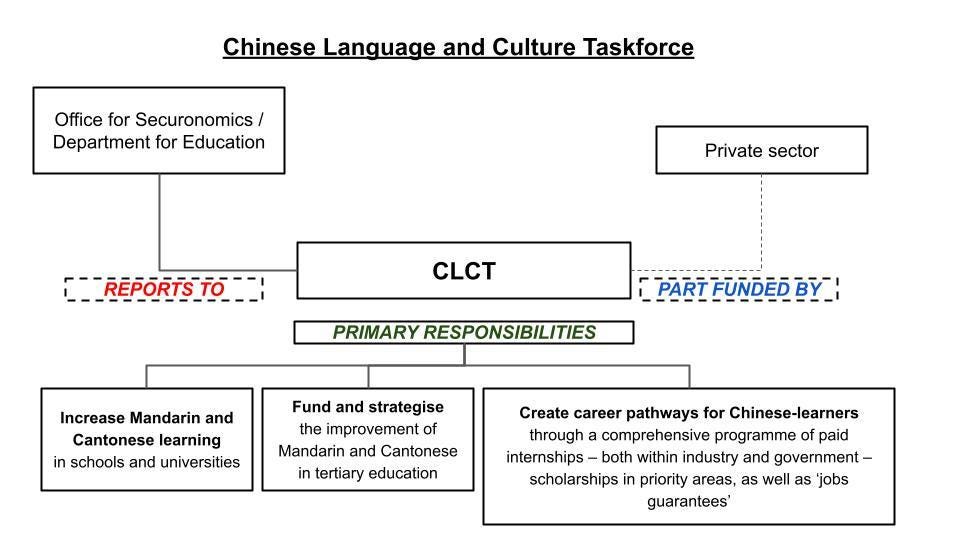

To this end, the Government could create a new Chinese Language and Culture Taskforce (CLCT) in recognition of the urgent need to improve the UK's China capabilities and build a pipeline of future leaders in this space.

The CLCT will work with the private sector to:

Increase Mandarin and Cantonese learning in schools and universities, and dovetail the existing programmes, having secured private sector buy-in to help fund programmes through auditing and reform initiatives such as the Mandarin Excellence Programme.

Reform the Chinese examination system at a secondary school level.

Fund and strategise the improvement of Mandarin and Cantonese in tertiary education, with a view to replacing Confucius Institutes in all our universities.

Provide seed funding to leading UK universities to establish/expand China-focused faculties, with a particular emphasis on interdisciplinary approaches (e.g. China studies alongside other relevant topics), seeking to crowd in long-term private sector co-funding.

Explore the possibility of establishing a UK branch of the well-regarded EU China think tank the Mercator Institute for China Studies (MERICS) – potentially with seed funding from the UK Government - as part of a wider package of deepening engagement with European partners (e.g. Erasmus, Project Horizon etc).

Create career pathways for Chinese learners, through a comprehensive programme of paid internships – both within industry and government – scholarships in priority areas, as well as ‘jobs guarantees’ attached to certain levels of attainment/proficiency to provide incentives for participants to pursue studies in these areas to the highest levels. Have Government-sponsored scholarships for students who want to study Mandarin or Cantonese at degree level.

Draw lessons from efforts and strategies in different sectors - including existing Civil Service Professions - such as the Government Geography Profession Strategy 2023-2036 aimed at “supporting and growing a diverse community of geographers and increasing the impact and influence of the discipline in government and beyond.”

Communicate

In Beijing to Britain’s view, one of the biggest failings of the current government is its unwillingness, or inability, to communicate clearly and consistently our approach toward China. This needs to be rectified as a matter of priority.

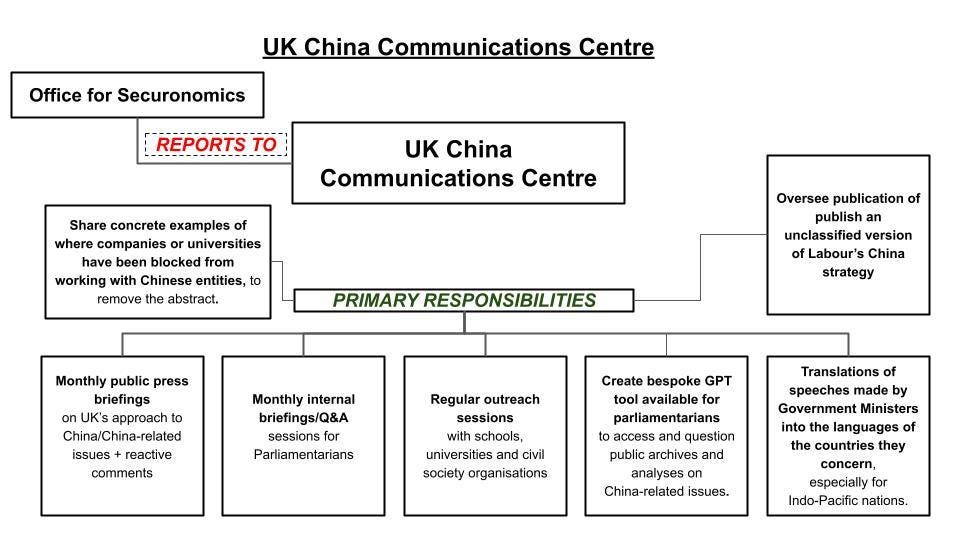

We suggest the creation of a professional and comprehensive communications function – UK China Communications Centre – which will ensure the UK’s approach to China is evidence-based, and communicated to the public, Parliamentarians, media, businesses and academia by subject-matter experts, as well as guiding public debate on China-related issues.

The CCC will provide:

Press briefings on the UK's approach to China/China-related issues – as well as offering reactive comments.

Regular outreach sessions with schools, universities and civil society organisations, working closely with organisations such as the Defending Democracy Taskforce (DDTF), the Research Collaboration Advice Team (RCAT), the NCSC and NSPA on public communications to share non-sensitive information in a concise and clear manner.

Sector-specific contact points – including advising businesses in those sectors on issues around the National Security & Investment Act and the National Security Act. This should include showing concrete examples of where companies or universities have been blocked from working with Chinese entities, to remove the abstract.

Create a bespoke GPT tool available for parliamentarians to access and question public archives and analyses on China-related issues.

Translations of speeches made by Government Ministers into the languages of the countries they concern, especially for Indo-Pacific nations.

The creation and running of the British Embassy in China’s website, which should be updated regularly, alongside the various Consulates throughout China.

Main point of contact with the Index of Independent China Experts (IICE) when appropriate

Working with the Securonomics Unit, commit to publishing an unclassified version of Labour’s China strategy - a publicly available, and practical, document for business, academia, civil society and others to be able to clearly understand the parameters within which they should be operating – within six months of entering government.

This will ensure the UK is aligned with the approach taken by our allies – many of whom have published their own China strategies – providing a basis for collaboration with like-minded nations, and Commonwealth countries, and for engagement with China itself

Challenge

Conduct a UK-China Audit:

Reporting to the Deputy Prime Minister, the Securonomics Unit to lead work on the Audit, working with external risk-modelling/-pricing expertise, and relevant departments – including the Cabinet Office, Foreign Commonwealth & Development Office, Department for Business and Trade, Ministry of Defence, and Department for Science, Innovation and Technology. It should also include representatives from the Agencies.

The Audit will be guided by an external expert panel, with a politically neutral chairperson.

The objectives of the audit will be to:

Identify sectors deemed “critical” to the UK’s (a) national security (b) economic security

Identify areas of “over-dependence” on China in “critical” sectors and an assessment made of the feasibility/costs of mitigation – including diversifying/“friend-shoring”, working with international partners, and/or (re)building the UK’s domestic industrial capacity, where necessary.

Compare the UK’s current levels of “over-dependence” to like-minded countries and identify global best practices in addressing areas of vulnerability, drawing – in particular – on the experiences of countries in the Asia Pacific region.

Sectors that should be covered in the audit include all 17 of those listed in the National Security and Investment Act, in addition to any further sectors/areas that are deemed relevant, either now or in the future.

Where the Audit identifies sectoral vulnerabilities, establish focused Working Groups with key allies and private sector companies to develop long-term shared plans for enhancing mutual economic security in these specific areas.

On the basis of the Audit findings, publish an unclassified version of the UK’s strategy towards Economic Security, alongside the government’s China Strategy.

In the medium to long term, publish a document comparable to the United States National Intelligence Council (NIC) Global Trends paper, outlining scenarios that UK political and establishment intelligence potentially foresee by a set date.

Ensure China is consistently held to account for its international obligations and responsibilities, including human rights and maritime law

Successfully challenging China involves consistently highlighting where the PRC is falling short on its human rights obligations both internally and in the wider international arena.

Establish a new Prime Minister-led dialogue on the International Rules-Based System, for the purposes of robust dialogue between two permanent UN Security Council Members over issues of shared concern, as well as holding China to account over its international obligations and responsibilities - including the Sino-British Joint Declaration, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR); the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), all of which China has ratified; as well as World Trade Organization (WTO) commitments on issues such as industrial subsidisation, protection of foreign intellectual property, forced technology transfer, and market access concerns.

Create, and fund, public research and analysis on how the PRC is or isn’t behaving according to its human rights obligations, in a similar fashion to the US State Department’s Global Engagement Center.

Identify any ‘gaps’ in current guidance for businesses looking to trade with China regarding issues such as human rights/forced labour concerns and supply chain due diligence.

When the PRC acts in a way that infringes upon the United Kingdom’s democracy, the Government should act with clinical punitive measures.

A ‘Sanctioned Dashboard’ could be created, which shows clearly which groups and individuals have been sanctioned, and what the material impact of those sanctions is estimated to be. Visitors should be able to see the name of the company/individual, every single sanction in place on them, and the estimated cost to them (e.g., areas they can no longer travel to, finances currently frozen by the British and allied Governments.)

Any Chinese entity or individual found to be committing an offence that damages the national security of any Commonwealth nation should be sanctioned by the British Government almost by default, with pressure exerted to bar them from operating in other Commonwealth countries.

More generally, Labour should cement the United Kingdom’s position as one of the leading P5 and G7 voices on holding the Chinese Government to account over illegal fishing, with a particular focus on advocating on behalf of smaller Indo-Pacific and African countries.

In a similar fashion to the Ministry of Defence’s public intelligence reports around the illegal Russian invasion of Ukraine, commit to publishing infographics and information relating to Chinese cyber campaigns or disinformation efforts.

The Government should commit to publishing annual updates on how many interventions and actions have been made under the National Security Act.

A similar public update from the National Protective Security Authority (NPSA) with regard to its portal should also be published.

A future Labour Government could continue the established practise of announcing cyber warnings with Five Eyes partners or allies.

With regard to defending free speech, and protecting Chinese and Hong Kong students and diaspora from intimidation, the Defending Democracy Taskforce (DDTF) should utilise the Hong Kong BN(O) talent pool, creating a fast-track Developed Vetting (DV) scheme for those who speak Cantonese and/or Mandarin.

On Taiwan, the Government should:

Challenge the Chinese Government’s rhetorical line around the initial agreements when it is presented ahistorically

Continue to encourage British businesses to build mutually beneficial relationships with Taiwanese sectors such as offshore wind, digital, and on organic products

Advocate for Taiwan's return to observer status at the World Health Organization (WHO)’s World Health Assembly (WHA)

More frequently co-sign reactive statements from partners such as the European Union or the United States regarding any PRC military action or grey zone behaviour that threatens the current status quo.

Compete

For the UK to succeed in the 21st century, we need to invest in our existing areas of strength - as well as compete for the industries, and jobs, of the future, leveraging Labour’s Green Prosperity Plan and new National Wealth Fund.

Enhance and formalise ‘clustering’ agreements between universities and local businesses all over the country – leveraging the UK’s new National Wealth Fund to invest in British industries, creating engines of regional economic growth, and providing a long-term return for the taxpayer.

Grow and invest in RCAT, enabling them to provide advice and insight into the clustering agreements as they develop.

Make sure the benefits of AUKUS Pillar II are realised throughout the UK’s various centres of excellence and universities.

Engage more assertively in World Trade Organization reform efforts, and establish new plurilateral groupings of like-minded, to better address China’s “gaming” of the existing international trading system. At the same time, explore ways to strengthen standards in new and existing trade agreements (e.g., CPTPP) on key areas of concern (e.g. treatment of State Owned Enterprises, and transparency requirements around industrial subsidies) to ensure a level playing field, allowing UK companies to compete effectively.

A Labour Government should continue to state all applications must meet the Auckland Principles, including the PRC.

Re-engage in multilateral and transnational organisations - including standards bodies - where China has made concerted efforts to take up leadership positions, ensuring the UK is actively challenging for these positions and supporting allies to do the same. Make sure the proper level of seniority is observed when British officials attend annual or important meetings of these organisations.

Ensure close collaboration with Advanced Research and Invention Agency (ARIA) in order to constantly horizon scan for new technologies and scientific breakthroughs that allow the UK to reduce dependencies on the PRC - like Perovskite solar cells or Northvolt’s new lithium-free sodium-ion battery - or project UK soft power and influence around the world (e.g. UK’s Humanitarian Innovation Platform working with MSF data sets and AI to reduce waterborne diseases in refugee camps).

Aggressively fund, promote and make a source of pride the UK’s artificial intelligence and quantum computing sectors – as part of a wider industrial strategy - with a focus on areas suggested in think tank Onward’s ‘Science Superpower’ reports.

Cooperate

Cooperation with China is a necessity. David Lammy has set out his vision for the FCDO as the “delivery arm” of Keir Starmer’s ‘missions’: “which means, above all, delivering jobs and growth” for the UK. Engagement with China will be critical to achieving this. At the same time, creating the conditions to do so in a way that protects national security and the UK’s values is essential.

Establish new bilateral Ministerial-level dialogue on climate change and green transition between the PRC and UK - as part of the dialogue, the UK and China will agree to collaborate on a number of ‘testbed’ projects in third countries (e.g. potentially Commonwealth countries), supporting green transition within those countries. The proposition should be that the UK and China will work together to fix an issue for third countries, with maximum transparency from the host country and the international community.

Engage with private sector firms and leading experts to fully understand the landscape around climate change and green technology cooperation – extracting the benefits of cooperation, while minimising risks, will be critical for Labour’s Net Zero plans. Examine where the UK has a competitive advantage, perceived exposure, what the risk tolerance is, and what - if any - plans there are to reduce said exposure. Following this, transparently set out recommendations and observations as part of a Labour China Strategy.

Establish new bilateral Ministerial-level dialogue on AI and Emerging Technology – with a particular focus on safety and standards-setting – building on the progress made at the November 2023 AI Summit at Bletchley Park and the 2024 Seoul Summit.

Labour could explicitly rule out a formal Free Trade Agreement with China – it is not the right approach for the UK at this time, while also recognising that “trade is clearly one area where cooperation is possible, and in our mutual interest” as described by Shadow Business Secretary Jonathan Reynolds.

Recognise the importance of China as a trading partner for the UK while seeking to rebalance our current trading relationship – launching a consultation with British business about what areas of enhanced market access with China would most benefit UK companies and workers – with a suggested focus on:

Greater access for UK companies in existing areas of strength (e.g. services);

Supporting the UK’s new industrial strategy;

Ensuring access for UK manufacturing, particularly in areas where China currently has a competitive advantage (e.g. Electric Vehicles);

Cooperation in support of the Green Prosperity Plan;

Creating greater opportunities for UK SMEs in non-strategic/lower-risk sectors, such as food and drink, where there is growing demand from Chinese middle-class consumers.

Concluding views

At its core, the purpose of foreign policy is to further a nation’s interests. To be effective as a Western democratic nation requires the ability to balance trade-offs, diplomacy, hard and soft power, and financial and societal stability. Clearly, the tools available to countries range in relation to their size, economies, governance, population, position or partnerships.

Often, foreign policy ends up being a case of settling on the least worst option. The world beyond the United Kingdom’s borders is not a balanced, efficient market, with each country achieving its own aims to its maximum level of satisfaction. This era more closely resembles an oligopoly, with a small number of nations setting the agenda, and dictating the future, of the others, with almost every nation trying to achieve its own goals. The traditional means of effecting change are under intense strain, and many of the world’s so-called ‘Global South’ countries are rightly pushing for their interests and policy goals to be furthered.

So what are the United Kingdom’s interests? This is a simple question that any diplomat, politician, policymaker or analyst should be able to reel off and answer. But ask around, and I suspect you will get different answers.

The United Kingdom has many legacy institutions and positions that give it an elevated status in its ability to influence others. Our overall strategic aims align closely - but not entirely - with the United States, and Five Eyes partners Australia, New Zealand and Canada. The UK is a member of the CPTPP, is a dialogue partner to ASEAN, and is in the AUKUS triumvirate. We have world-leading companies sitting in industries on the cusp of defining the next century - quantum and artificial intelligence being just two. We have centuries of business acumen, a truly excellent gathering point of intelligent people in one city, and a globally respected legal system. Many of the digital deals we have signed across the Indo-Pacific region will bear fruit in the coming years too, and the UK’s renewed push into the five Stans and Mongolia remain under-appreciated. London sits at the heart of the Commonwealth, an under-utilised grouping comprised of over a third of the world’s population.

But something is going wrong. The relationship between Government, Parliament and Whitehall is not working, and the reality that foreign, domestic and industrial policy are interlinked has not sunk in. This is not just in relation to our bilateral relationship with China, but speaks to a wider inability to see the world for what it is, rather than what we want it to be.

Things can, and must, change. This is not a time to smuggle indecision dressed up as caution, or to hope things just work out. It is time to reform the systems which underpin how we understand the world. I hope this paper provided some provocative, granular ideas for what a future Labour Government could do differently on the China front, and where it could replicate at speed any of the suggested policies and systems that work.

It's been a ride!

“Who has not felt the urge to throw a loaf of bread and a pound of tea in an old sack and jump over the back fence?” John Muir